In view of the necessary transition toward a carbon-neutral society, the role of Citizen Energy Communities (CECs) in Europe could be very relevant. Developing a technical and business ecosystem for integrated energy services for CECs is the core objective of NEON (Next Generation Integrated Energy Services for Citizen Energy Communities) project.

The European Union is increasingly committed, through a series of measures, to empowering consumers to foster energy transition. This is a key element to reach the climate goals established by the European Green Deal. However, there is room for improvement to fully unlock the energy efficiency and flexibility potentialof consumers’ communities: a developing framework needs to set out practicable solutions, on contractual and financial aspects.

Focus on the Economic Sustainability of Energy Communities

The energy transition requires the involvement of citizens, institutions and local companies in energy projects carried out also by energy communities. The aim is to ensure that these projects provide environmental and social benefits that have a positive impact at the local level. At the same time, the energy communities must show clear economic sustainability.

Within the scope of the NEON project, ItaSIF together with its project partners conducted an analysis that considers the actual and expected costs of four pilot areas in Spain, France and Italy. The analysis identifies suitable financial structures to ensure pre-financing of initial energy efficiency interventions and payback through revenue streams.

The outcome of the study was a public report focused on how to attract private capital under the concept of CECs and how to minimize the business risk for the involved actors. This article will point out the major results.

Ensuring Cost-Effectiveness of the Service Offer: Private Funding Opportunities

There is a variety of private funding instruments available to create and support energy communities and their ancillary services. First of all, there are instruments of equity finance and self-financing. They imply providing ownership rights to the source of financing, splitting risks between the funder and the organisation that receives funds. It is important to underline that equity finance does not necessarily produce profits.

Unlike equity finance, debt financing instruments – such as leasing, soft loan, Energy Efficient Mortgage (EEM) or green bond (if an undertaking or a local authority is involved) – do not have a direct impact on ownership structure of the CECs. There are a few drawbacks: energy communities in their early stage may face difficulties to access debt markets and interest rates (i.e., the price of capital) could be perceived as too high in relation to services offered. Moreover, lenders may affect decisions of CECs towards more profitable services, paying less attention to environmental and social aspects.

Crowdfunding is another interesting private funding scheme, and it is becoming a feasible alternative to classic loans and mortgages in financing energy-related projects. It relies on capital collected from many private investors (both individuals and corporates) through an online crowdfunding platform.

Another funding scheme is represented by Energy Performance Contracting (EPC). In this innovative on-bill financing scheme for energy efficiency investments, the contractor gives a financial guarantee for the expected energy savings on a project. Remuneration is closely linked to the success of the interventions carried out by the supplier that can focus on both the energy saving of the project and the use of renewable energy.

Dealing with Risks in Energy Efficiency Financing

Investment risks require special attention. It is possible to identify a variety of risks that could reduce profitability and endanger the successful implementation of energy efficiency and energy services projects, also in the context of energy communities.

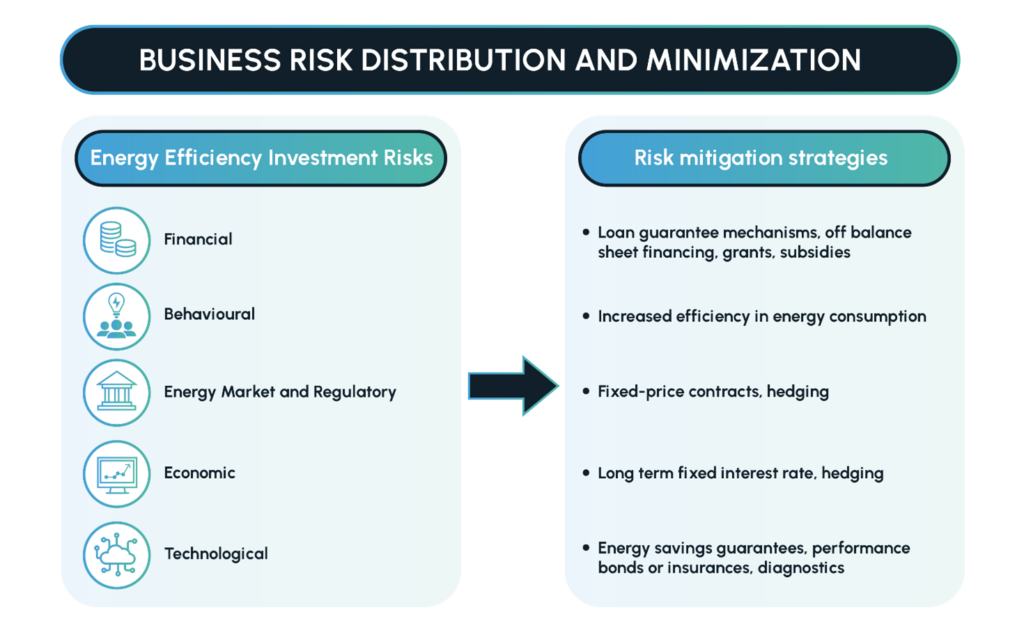

They must be considered by financial institutions and can be classified into the following categories:

- Financial risk (that indicates the financial capacity of the borrower to pay off his debt),

- Behavioural risk (represented by the behavioural biases of end-users regarding how they consume energy),

- Energy market and regulatory risk (that includes energy prices and taxes volatility and request for issuing project permits),

- Economic risk (linked to the macroeconomic environment of the country in which a project is settled), and

- Technological risk (that refers to the technical aspects of the installed equipment and the skills of the workers).

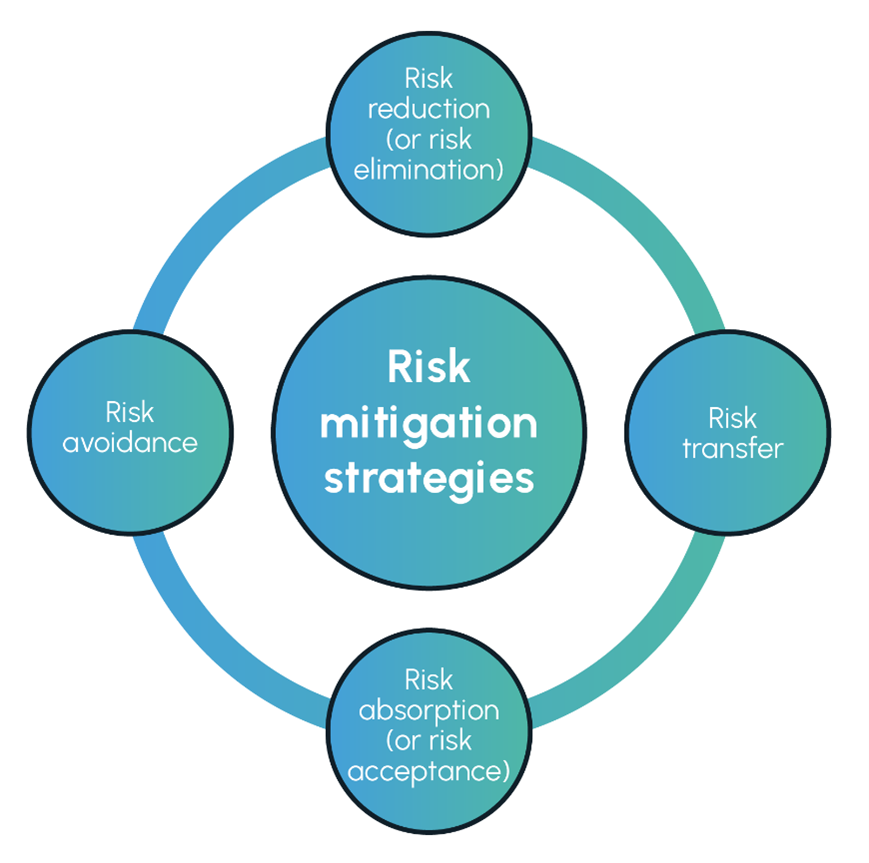

There are four main risk mitigation strategies that could help reduce the impact of each risk factor or the probability of occurrence in the project.

These risks and the strategies to minimize them can be summarised in the figures below.

Source: Italian Sustainable Investment Forum (ItaSIF) elaboration

The goal of the risk reduction strategy is to decrease the impact or probability of risk occurrence by planning specific measures. The risk transfer strategy refers to transferring risk from one party to another (e.g., through insurance contracts). According to the third one (risk absorption), the impact of risk is considered acceptable: no actions are required for reducing it. The risk avoidance strategy can be applied if the probability of risk occurrence exceeds a present threshold: in this case, the project should be abandoned, or its objectives should be changed.

A more in-depth analysis of all these aspects is available in the NEON Project Deliverable 2.3. It is the third deliverable of WP2 “Contractual and financial aspects of cross-service integration” and a result of Task 2.3 “Service financial structure and business risk distribution”.

Italian Sustainable Investment Forum (ItaSIF)